News

We often speak of mountain top experiences: those moments when God is powerfully present, when we feel that we have stepped outside of the humdrum and the ordinary and touched the divine and the eternal. Both readings this morning recount such an experience. In both they take place on a mountain top, above the concerns of the everyday.

In Exodus 24:12-18 it is only Moses who is permitted to draw near to God, the rest of the people must stay at the distance. In Matthew 17:1-9, however, Jesus takes people with him. Here, instead of the “devouring fire” seen by Moses on the mountain, they see Jesus transfigured by the fire, the light and glory emanating from within him.

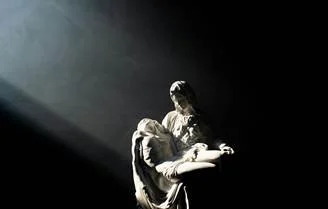

The disciples are scared out of their wits but Jesus restores them with a touch. Here God is no longer separate from humanity, no longer distant and other but is deeply and intimately enmeshed in and with humanity.

God does not remain on the mountain top, God accompanies them back down the mountain into the world of the everyday. Here they are to learn that they too can be transfigured, soaked through with the love and the will of God. And, being filled with Christ, recognise Christ in others and in the world around them.

God is not for special times and special places, God is for all times and all places. Shining through the world, shining through each and everyone of us, calling us to reach out our very human hands that through them God might bring healing and renewal to a needy world.

No worries! Who is Jesus kidding when he tells us not to worry in Matthew 6:25-34. Worry is, after all, an essential part of life, it helps us to focus on what matters. And that is the point Jesus is making, what are we worried about and what does it reveal about what is important to us?

When we focus on ourselves, our own survival, success and security, we focus what we lack, what we have not got, what we might lose. Instead, Jesus asks us to shift focus and concentrate on the kingdom of God. At first this might appear to increase the number of things to worry about: no longer do we worry just about our own health and well-being but that of the whole planet and all the people in it. Indeed, the letter to the Romans, 8:18-25, compares the work of encouraging the kingdom of God to the pains of labour. Yet, the pains of labour are bearable because we know that we are bringing new life to birth.

The door to happiness opens outwards and involves a certain level of self-forgetfulness; an ability to look beyond our own lives and see how they are intimately connected with lives of others and with the whole of creation. To the extent that we can lay aside our own concerns and look to the concerns of the Kingdom, we learn to focus, not on what we don’t have but what we do and, more importantly, how we can use it.

Today we celebrate the last of the Epiphanies: those moments of sudden wonder and understanding when something extraordinary is revealed to us. In these moments Christ shows us not only who he is but also who we are. Of all the epiphanies, the last is probably the most ordinary: a young family go to worship and are welcomed by a couple of old folk. Yet is also the one that is perhaps the most helpful in showing us how to become who God made us to be. In Luke 2:22-40 the revelation of God’s presence here with us is only made when different people are gathered together. It is when people of all ages, genders, class and status are united, that we see God united with us also. God is made present among us. The path to God is found in embracing each other and discovering what unites us.

Today we celebrate the Conversion of St Paul, who teaches us that “by grace you have been saved by faith”. Yet both our readings express something of the doubt and confusion involved in the life of faith. In Acts 9:1-22, Paul, once so certain of his faith, is blinded, unable to see, not knowing where he is going. Ananias is also confused and uncertain when God calls him to visit the man who has been an enemy to him and his fellow believers. It is Ananias faith, his ability to take a risk and follow God into the unknown despite his doubts, that brings healing, sight and faith to St Paul. In our gospel, Matthew 19:27-30, the disciples are also experiencing doubt: they have taken the risk of faith, they have left everything, yet they are uncertain of their future.

They, like we, want security, they want to know where they are going. We like to feel in control of our own lives and it is often only when the rug is pulled out from beneath us, when, like Paul, we are groping blindly and are unsure of the way to go, that we place our trust in God. Wealth, status and health are ephemeral but the merciful love of God is enduring.

When we feel lost and disorientated by life’s events, this is not the end of faith, but it’s beginning.

Jesus’ ministry has a very low-key start in John’s gospel. In Mark he silences a demon, in Matthew he teaches a vast crowd, in Luke he preaches in the synagogue but in John 1:29-42, he just stops and talks to a couple of people, asking them what they want, what it is that they, that we, are seeking? What is it that we need?

There are parallels with the way in which the suffering servant, in Isaiah 49:1-7, starts with the needs of others. Whether the servant refers to an individual or to a wider group of God’s people the answer to their own suffering and seeking is to be found in serving others.

The two disciples respond to Jesus with a question of their own: where can we find you? Jesus’ reply, come and see, is an invitation. In the other three gospels Jesus begins his ministry with an action or a statement which shows others who HE IS but here, in John, he invites us to join him so that we might discover who WE ARE.

Just as the people of God who have suffered exile and defeat in Isaiah are offered healing and restoration through engaging in the needs of those around them; so Jesus invites us to find what we seek by participating in God’s work of healing and restoring the world around us.

Who do we think we are? Epiphany is the season of revelation; the stories that reveal Christ’s true nature also reveal our own identity as his siblings in the family of God. Today, as we mark the baptism of Christ we remember that we too are baptised in the same spirit.

In our gospel, Matthew 3:13-17, John does not want to baptise him, yet Jesus insists so that we might not be afraid to follow him into deep waters. Just as the Spirit moved over the waters bringing creation into being, so the spirit moves over the waters of baptism recreating us.

The voice of God calling Christ his beloved child is for us too, we are claimed and renewed and anointed so that we might follow Christ, carrying the spirit of God into the world and working for the renewal of all people and the whole of creation.

The feast of the epiphany tells the story of the magi travelling from the east to pay homage to the Christ child, Matthew 2:1-12. These visitors echo the prophecy of Isaiah 60:1-9 that “nations shall come to your light, and kings to the brightness of your dawn” and signal that Christ is a gift, not just to the people of Israel but to all peoples of all nations, faiths and cultures. The gifts they bring speak of the nature of the Christ child: gold for ruling, frankincense for holiness and myrrh for dying.

But this story is not just about Christ’s true nature, it is about ours. At our baptism we too are anointed as leaders, priests and gifts. Just as the gifts given to the infant Jesus symbolise how he will live his life as a gift to God’s world, they show us how we should live. We too are gifted and our gifts are only of any use if they are used for all of us. The prophet Isaiah, 60:1-9 calls us to “arise, shine for your light has come”. The light that shines on us is to become the light that shines from and through us. In sharing this light we lighten the path that leads to a home for all God’s people.

Just four days ago the angels were proclaiming glory to God in the highest and peace to his people on earth, yet today we hear mothers weeping over the death of their children. Had anything changed in the time between the mothers weeping in Jeremiah 31:15-17 and those still weeping in Matthew 2:13-23? Has anything changed since? Mothers’ still weep, innocents are still slaughtered, did Christmas change anything?

The long story of salvation records violence breeding yet more violence: the Israelite children were slaughtered by Pharoah; their freedom was bought by the slaughter of the Egyptian children; they used their freedom to slaughter yet more children, this time Canaanites. When Christ is born Herod slaughters the infants in Bethlehem and Mary and Joseph flee to Egypt, the land of their enemies, and find refuge there. But, something has changed: when Christ returns from Egypt he does not answer violence with yet more violence, instead he submits to the violence of the world to reveal to us a power stronger than violence, the power of love.

Christ’s birth and death and resurrection reveal to us that violence does not come from God and is never sanctioned by God. What God offers us in Christ is the chance to be changed, to become children of God. So that we might receive a power far greater than violence, the power of love. Love is the only power strong enough to defeat violence. Love is the only power great enough to transform an enemy into a friend.